For over a month I’ve been taking part in The Sunday Salon hosted by Deb Nance at Readerbuzz. So far it’s been a huge success and I’m striving to make it a regular feature. So here’s another post.

For over a month I’ve been taking part in The Sunday Salon hosted by Deb Nance at Readerbuzz. So far it’s been a huge success and I’m striving to make it a regular feature. So here’s another post.

I finished Frank Blaichman’s Rather Die Fighting: A Memoir of World War II as well as Adam Hochschild’s Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. I read both books for Rose City Reader’s European Reading Challenge.

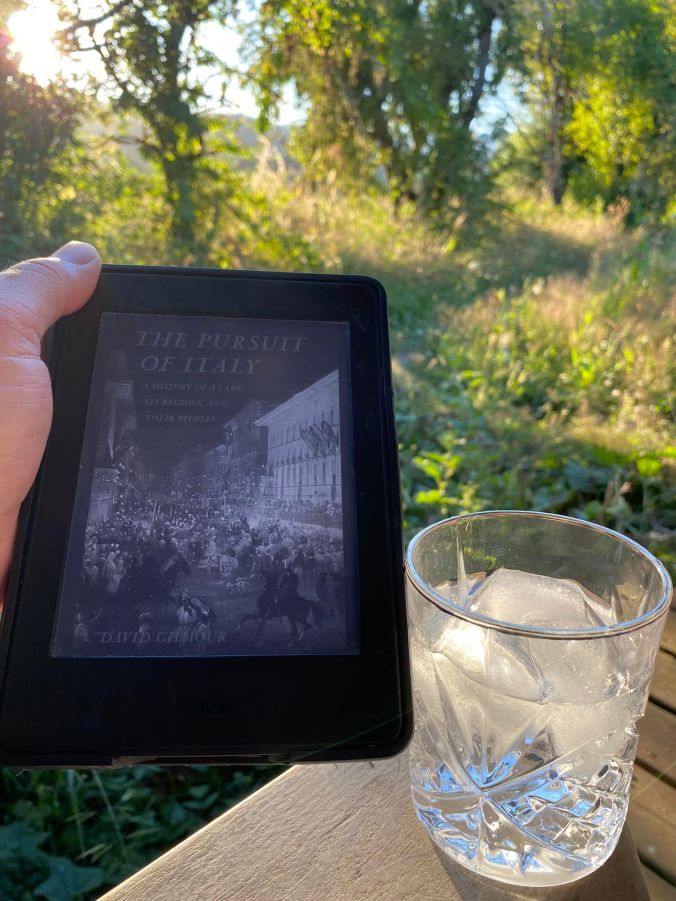

Late last week I started David Gilmour’s The Pursuit of Italy: A History of a Land, its Regions and their Peoples. So far it’s shaping up to be an excellent book and perfect for the European Reading Challenge. I’ve also resumed reading Stuart Jeffries’s Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School.

Listening. With so many things going on in the world there’s been no shortage of material for my favorite podcasts. Despite this extensive list I feel I should be listening to much more.

- Fresh Air – “Inside A Powerful MAGA Messaging Force“, “How the Mexican Revolution Shaped the U.S” and “Life In a Sex Cult”

- Friendly Atheist – “Who’s the Real Hate-Preacher?”

- Fever Dreams – “Alt Right Reservoir Dogs Feat and Matt Ford”

- The Bulwark- “David Jolly: DeSantis Has the Hottest Hand in Politics Right Now“, “Michael Steele: Fighting the GOP Crazification” and “Adam Kinzinger: We’re Going to Prove What Trump Knew during Those 187 Minutes“

- The New Yorker: Politics and More – “How White Christian Nationalists Seek to Transform America” and “What Precedents Would Clarence Thomas Overturn Next?”

- MindShift – “Thy Kingdom Come: Exploring Christian Internationalism with Dr Melani McAlister“

- The New Abnormal – “Republicans Now Have an Incentive to Be Terrible” and “The REALLY Shocking Moment From the Jan. 6 Hearing”

- The Daily – “On Abortion Laws, It All Goes Back to 2010“, “How Sri Lanka’s Economy Collapsed” and “A View of the Beginning of Time”

- The Weeds – “What the hell is up with SCOTUS?”

Watching. Mr. Robot continues to entertain with its crazy plot twists, great writing and superb acting. I also caught a few episodes of Stranger Things. On Thursday after watching the January 6 Hearings I followed it up with an entertaining and informative episode of the Lincoln Project’s The Breakdown.

Everything else. Yesterday my professor buddy and I had some great wine as we took in the amazing view at our favorite local winery. The weather at my place has been nice of late so I’ve been reading on my porch. While I’ve been drinking coffee in the mornings, in the evenings with my book I’ve been known to enjoy an adult beverage or two.

Well, another year of

Well, another year of